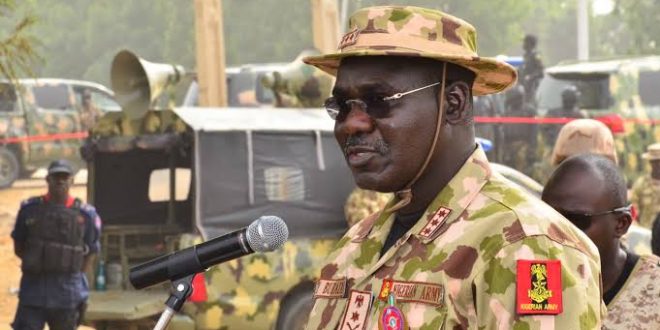

Whether the Chief of Army Staff, General Tukur Buratai, failed to think through his statement last Tuesday condemning Nigerian military troops who are on the frontline of fighting the Boko Haram insurgency or he was just being magisterial like all bosses do, the import and symbolism of that waffling condemnation, it will seem, are far too fatal than he probably can guess. His allegation against the hapless soldiers, shunned of hyperboles, is treason. At the opening ceremony of a workshop tagged “Transformational leadership” which was organized by the Army Headquarters Department of Transformation and Innovation, which held at the Army Resource Centre in Abuja, Buratai had said: “It is unfortunate, but the truth is that almost every setback the Nigerian Army has had in our operations in recent times can be traced to the insufficient willingness to perform assigned tasks or simply insufficient commitment to a common national/military course by those at the frontlines. Many of those on whom the responsibility for physical actions against the adversary squarely falls are yet to fully take ownership of our common national or service cause.”

Buratai’s allegation has provoked critical discourses. Broken down to its basest ingredients, the Lieutenant General was simply accusing his troops of treason. If anyone says that the claim by the Nigerian state, represented by its No 1 Army Commander, that the multiple killings of Nigerians in recent time by an apparently more coordinated, closely-knit and more forward-looking Boko Haram fighters, as well as the shrouded, yet loudly sounding sad news of the killing of hapless soldiers in the last couple of months, were as a result of “insufficient willingness” of the soldiers, isn’t an accusation of treason, then we may have to break open the Thesaurus to find its hidden semantics. So, are these young men and women engaged in treasonable dissent against the Nigerian state or the state is mortally unfair to them?

By Festus Adedayo

South Daily

South Daily